Credit expansion banking creates boom and bust cycles

There is a fascinating contradiction at the core of capitalist economic systems

Background

My last post gave a brief overview of what credit expansion banking is and how it works.

This post describes how credit expansion banking creates booms and bust cycles. Which on occasion can accurately be described as “manias, crashes, and panics”.

As I mentioned in my last post, credit expansion banking has enabled enormous wealth creation since it arrived in Europe about 600 years ago.

I have personally come to believe that credit expansion banking is the second most significant technological development of human civilization, the first being our ability to use and control fire. Seriously. It’s that important.

It’s that important because it has enabled most aspects of modern civilization. Without the ability to finance expensive projects that credit expansion banking enables, I believe we would still be living in the horse drawn hand cranked world of the middle ages.

Developing and exploiting new technologies requires financing. Credit expansion banking is the core mechanism of that financing.

But… The genie extracts a price

I love the metaphor of the genie here. Ready to grant enormous riches. But, there will be a price to pay.

As regards credit expansion banking, the genie extracts a price in exchange for the riches it bestows because of an inherent contradiction at the core of credit expansion banking, and credit expansion backing sits at the core of capitalist economic systems.

That contradiction is that our money simultaneously is, and is not, in the bank.

Your money is in the bank

People think that when they deposit money at a bank, the bank holds the money and as you come in and ask for me, they hand it back.

While we talk about banking that way, that’s not how banking works.

Your money is not in the bank

In law, when you deposit money with a bank, it’s no longer YOUR money.

What you have is a demand deposit. An IOU. Or more accurately a collection of IOUs as you can withdraw fractions of what you deposited.

To you, the demand deposit is an asset, but the asset isn’t money per se, it’s the demand deposit.

But to you, it’s as good as money. When you use your ATM card at a store to buy something, they take the money out of your account.

To the bank, deposits are liabilities, as they can be withdrawn at any time. Upon demand.

So where does the money go?

The money becomes the property of the bank, and they do with it whatever they want within the limits of the laws and regulations of banking.

Maybe some gets converted into cash and the cash goes in the vault. Maybe they deposit some at the central bank (to increase their reserves). Maybe they buy Treasury bonds. They have options.

But when you withdraw money, you get it, right?

Yes.

But… If everyone shows up at once to withdraw money, the bank is in serious trouble. They never have enough on hand to handle that.

In a credit expansion banking system, no bank is immune from “too many” withdrawals in too short a time span.

A very brief primer on banking

Banks serve two main functions. Making loans and settling payments.

Making loans

This is a main way banks make money. Miscellaneous fees such as late fees and processing fees etc are income to the bank, but interest on loan payments is the main source of income to banks.

Settling payments

Almost every purchase made is paid by moving money from one deposit account to another.

You buy groceries. You have a bank account. So does the store. When you pay for your groceries, money is withdrawn from your account and deposited in theirs.

When both you and the store use the same bank, that payment clears, or settles, at that bank.

When you and the store use different banks, the payment settlement occurs between banks. Your bank withdrawn money from your account. Your bank sends money to the stores bank. The stores bank deposits money into the stores account.

That is an interbank settlement. For purposes of interbank settlements, banks keep money on deposit at the central bank. They’re called reserves. Which really just means deposits at the central bank. Banks send each other settlement payments to facilitate the fact that all of us in the economy bank at different banks.

I find it useful to think of central banks as the bank where banks bank.

International settlements follow a similar process.

When someone who buys something banks at bank A in one currency (banking system) and the merchant they buy it from banks at bank Z in another currency (banking system), such as a Wells Fargo account used by a US resident is being debited and a Royal Bank of Scotland account being used by a resident of Scotland is being credited, another bank comes into play.

It’s the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

They’re kind of an international central bank for central banks.

What does this have to do with boom and bust cycles?

Pretty much everything, as we’ll see soon.

The issue is not on the boom side of things. When economies are booming and money supplies are expanding, there is by definition enough money to go around, as it’s being created “as needed”.

But, during bust cycles credit money creation decreases, often reverses, money supplies contract, and there is less money to go around. In extreme cases there is literally not enough money in the economy for all the commerce that could happen to happen.

This occurred during the Great Depression.

Economic equilibrium is like unicorns

We can talk about it. We can believe it exists. We can on occasion even think we’ve seen it.

We believed in economic equilibrium for centuries. Some still do. The belief was that economies reach equilibrium at full employment. And when economies “fall out of” equilibrium, they return to equilibrium at full employment. It may take time, but it happens.

But now we know it doesn’t.

The main way economic equilibrium is like unicorns is that neither actually exist.

Figuring this out was not the work of one person, but rather the work of several people over decades. But one person fairly recently in the accumulation of knowledge did such a good job documenting this that the model he developed is widely used and referenced.

His name was Hyman Minsky1 (born 1919 - died 1996) and the model he developed shows that financial instability is an inherent feature of capitalist economic systems.

The model he developed is named the Financial Instability Hypothesis2.

The cause of instability is stability

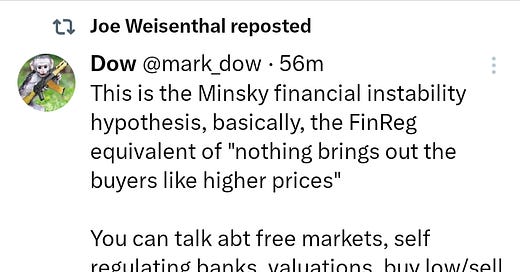

I’ll go into more detail soon, but this tweet explain Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis using the fewest words of any explanation I’ve ever seen.

Financial instability is created by debt financed investment

Much of what I write below is from the Book “Why Minsky Matters” by L. Randall Wray. I have the 2016 edition from Princeton University Press.

Where direct quotes are used, they’re quoted.

“The procyclical behavior of bank lending amplifies the business cycle, increasing the thrust towards instability.”.

Financial instability occurs because three things happen:

Increases in demand preceed increases in production.

Expanding production requires investment.

Such investment is done with borrowed money.

Demand goes up

People are spending money. They want more goods and services. To capture that demand, firms need to ramp up production.

Which costs money.

If a firm has cash they can use it.

But almost always firms finance expanding production with borrowed money.

Demand for loans goes up. Banks “produce” money (literally).

Increasing production makes more money for the firms.

Increasing loans makes more money for the banks.

Everyone’s making money.

Standards get looser

Everyone’s making money. But they could be making more.

“During an upswing, profit-seeking firms and banks become more optimistic, taking on riskier financial structures. Firms commit larger portions of expected revenues to debt service. Lenders accept smaller down payments and lower quality collateral.”.

So as not to miss out on opportunities to make hay while the sun shines, firms make more use of short term debt that needs to be refinanced (rolled over) at some point.

Economy heats up

More money, more production, more everything. People get raises. Shareholders get dividends. Demand grows, production follows.

And that lag between “demand grows” and “production follows” is a gap in the armor of financial stability.

It causes prices to be bid up a bit. For goods, for services, for wages.

The general level of prices increase faster than policy makers are comfortable with.

Central banks raise interest rates

Generally not by much, but a little. And this means when firms roll over their short term debt, their monthly payments will be higher.

Firms who expanded with debt (pretty much everyone) now have lower net margins as a result of higher interest expenses.

The financing for expanding production now costs more.

Financed positions became a little more fragile.

For most firms, this is fine

Income to most firms is enough to make all debt payments when they come due, principal and interest.

But some firms stretched themselves thin

And their income is enough to meet their interest payments, but they are unable to pay down their principal, which means that debt will need to be refinanced when it comes due.

And some firms stretched themselves too thin

To where even making their interest payments requires more debt. These firms are fiscally speaking, “living on the edge of the abyss”.

As the boom continues, debt payments cost more

By cost more, I mean take up an increasing share of firms income. When more money is needed to pay debt, less money is available for everything else.

As making those debt payments takes up a larger share of income for more firms, more firms find themselves “living on the edge of the abyss”.

Debt defaults become more frequent

During boom phases debt defaults are rare. But as more and more firms find themselves challenged to make their debt payments, defaults start to rise.

Banks tighten lending standards

In response to rising debt defaults, banks raise their standards for making loans.

Debt refinancing denials increase

Firms who need to periodically roll over or refinance short term debt are now facing higher standards for doing so, which some of them do not meet.

Firms who can not roll over debt must cut back

Reduce production, lay off staff, maybe even sell assets. They simply do not have sufficient income to meet their current expenses, and something’s gotta give.

Spending slows, orders to suppliers drop, people lose jobs

And because an economy is a complex web of financial transactions, as more and more firms reduce spending, the slowdowns spreads from firm to firm.

Spreading becomes contagious

The downswing is now in full swing. Sometimes it’s gradual. Sometimes it’s abrupt. How quickly it happens depends on a lot of factors.

We hunker down

Because what else can we do?

Then sometime later, demand goes up

And we do it all over again.

Production, speculation, same cycle

What I’ve described above is a production based business cycle, and while these cause pain during the economic contraction, these cycles occurs with speculative assets (stocks, bonds, and real estate) as well.

And when those bubbles burst, economic contractions are both big and fast.

The 1929 panic was a massive and almost overnight financial contraction caused by a lot of people having bought stocks with debt.

The 2008 financial crisis was a massive and almost overnight financial contraction caused by a lot of people having bought what are called Mortgage Backed Securities with debt.

The key phrase being “with debt”.

Minsky moments and doom loops

To illustrate how widely Minsky’s model is now used, in the language of finance and investing, there is now something called a Minsky Moment3.

It is a sudden and catastrophic collapse of asset prices after a period of growth and stability.

Another aspect of these cycles is named is the Doom Loop.

“In economics, a doom loop describes a situation in which one negative economic condition creates a second negative condition, which in turn creates a third negative condition or reinforces the first, resulting in a downward spiral.”4.

In closing

In modern capitalist economies, almost all money in circulation is debt. By which I mean it was created by a bank when they funded a loan. Almost every dollar (or pound, or yen, or euro, or whatever) is owed by someone to a bank.

And the business cycle Minsky describes so well is “baked into” such credit money monetary systems.

Accepting the riches the genie bestows on us extracts a price.

The taming of fire provided us with enormous advantages. But when it gets out of control it burns everything down.

Credit expansion banking also provides us with enormous advantages. But as with fire, when it gets out of control, it burns everything down.

The one thing I would question here is, is it really private banks that should be deciding how our credit is expanded? They take a pretty big skim of the economy for it, have almost no interest in funding socially useful schemes, have little incentive to avoid harmful ones, and they do pretty well out of both the boom and bust cycles - during the bust cycle, they foreclose on real assets