Background

I mentioned in my prior post that almost all the money in modern economies is created by banks1, and only a fraction of money is created by currency issuing governments (by the central bank).

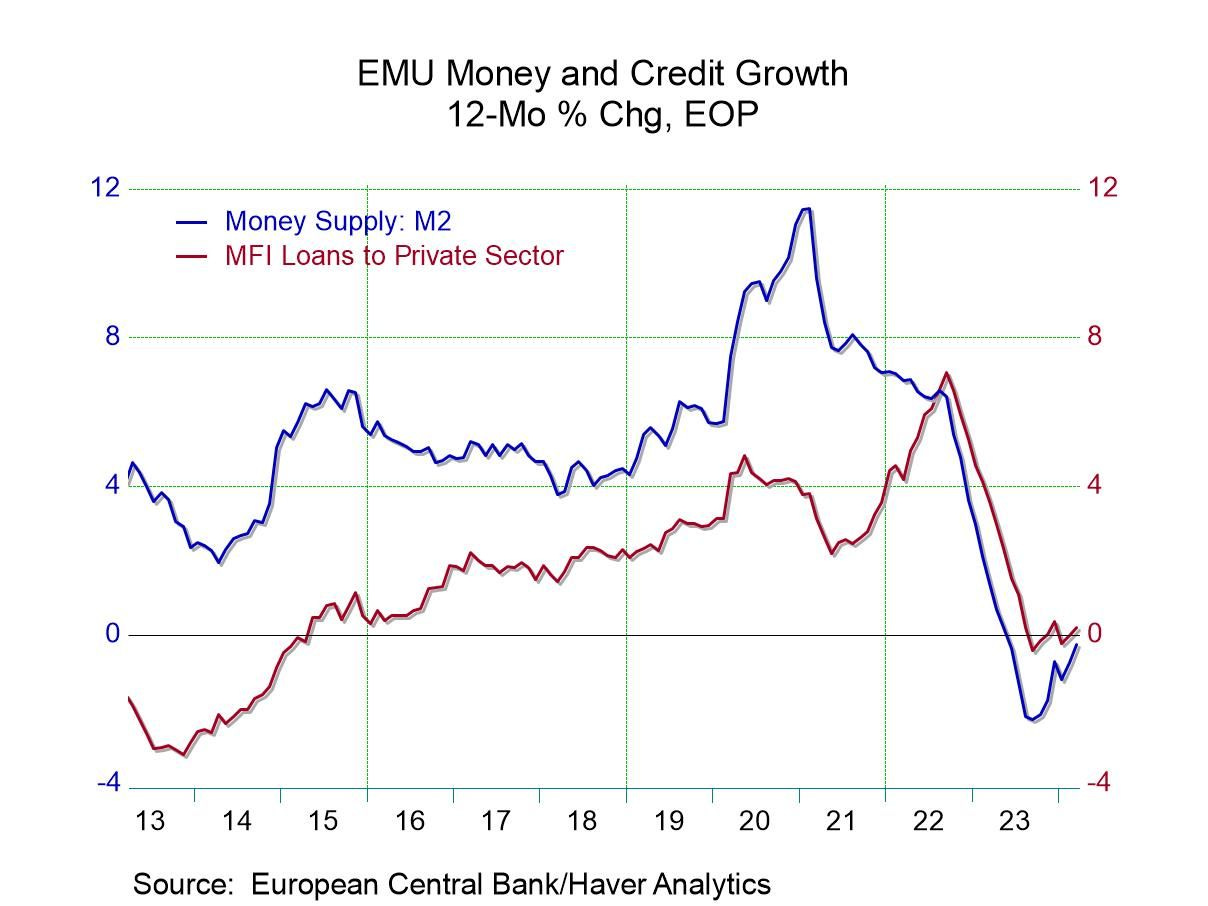

The chart below2 shows credit growth and money supply growth for the European Monetary Union (the Eurozone) and as you can see, except for the period where central banks were creating money like crazy during the Covid shutdown, the two correlate tightly.

Modern economies include…

From a high level perspective, modern economies include a fiat currency3, exchange rates that float relative to other fiat currencies4, and a credit expansion banking system.

The institutions who run this system include a national legislature (who make the rules), a national treasury (the federal governments finance department), and a central bank which supports that credit expansion banking system.

That last one is hugely more important than those few words might imply.

It can be helpful to think of banking as being a franchise, where the central bank is the franchisee and the commercial banks are the franchisors.

Short detour: Exceptions to what I’ve said above

Now we’re taking a slight detour to discuss a few exceptions to the above

In the Eurozone there are 20 legislatures, 20 treasures, and 20 central banks who share responsibilities in ways I have yet to learn.

Some countries do not issue their own currency, but instead use a currency issued by another country. Examples are: Ecuador, El Salvador, Panama, Timor-Leste, Palau, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, the British Virgin Islands, and Turks and Caicos, all of whom use the US dollar as their official currency. Even the British Virgin Islands, which I think is funny.

There are 14 counties in Africa with colonial ties to France who use a currency (the CFA franc5) that has an exchange rate which is pegged to the Euro and is guaranteed by the French treasury. This one I do not find funny as this structure is seemingly forced upon them. It started in the 1930s during colonialism and was not dismantled after independence.

Credit expansion banking is weirdly not well known

People complain about the size of national debts. They’re too big, they’re inflationary, wasteful government spending, etc, etc.

And most people who complain about national debts seem unaware that almost all the money we use is created by banks making loans6.

Yet almost all money is credit money

And that the amount of bank created credit money is so large that sovereign money (national debts) is tiny by comparison.

So… if the very small fraction of the money supply which is the national debt is very concerning, why is almost all the money we use (the bank created credit money) not even worthy of mention?

How much money should there be?

Wouldn’t a better concern be that an economy contain enough money, but not too much?

When an economy contains too little money, economic activity that creates wealth does not happen, for lack of the medium of exchange. This occurred during the Great Depression. In fact, when you model monetary flows you can see that a severe monetary contraction preceded the Great Depression7.

When an economy is at maximum productivity capacity, no amount of extra money can or will increase the productivity capacity, so more money will create the “too much money chasing too few goods” that causes inflation.

So, in regards to how much money an economy should contain, it would seem there is a Goldilocks zone of “enough but not too much”.

But how much is that?

Can we tether money creation to economic opportunities?

Yes we can.

When an entrepreneur has an idea for how to generate more wealth, we can increase the money supply to support that economic activity.

As some of those ideas work, we can increase it more.

As some of those ideas fail, we can decrease it.

A credit expansion banking and money system is one where the amount of money in the economy expands and contracts with demand for credit8.

When and how did we start credit expansion banking?

Fractional reserve banking was the earlier/earliest form of credit expansion banking, and it seems as if it started without any kind of central plan.

There is evidence to suggest that fractional reserve banking was practiced as early as the 7th century in parts of the middle east, and was practiced by the Medici Bank in Florence in the 15th century, but the practice became very popular in Europe in the 17th century.

The origin story is that goldsmiths worked in gold (duh?) and owned safes during as era when gold was the primary form of money.

People kept both gold jewelry and gold money in safes at goldsmiths, who by virtue of working in gold became bankers.

As fetching gold from the jeweler every time you needed to buy something was inconvenient, “gold certificates” were issued representing the gold in the safe.

At some point a jeweler or two or two hundred noticed that gold redemption was rare, and that people were happy to use the gold certificates in place of gold money.

So they started making loans in excess of the amount of gold they had in storage.

Which meant the amount of money in circulation expanded when loans were made, and contracted as loans were paid down.

Presumably when bankers saw goldsmiths making money this way, they adopted the practice too.

More money in circulation, more economic growth

There has also been a tight correlation between the amount of money in circulation and the amount of economic activity.

Simply put, economic growth decreases as the money supply contracts, and can increase only when the money supply expands.

But, there is a price to pay

I read a book about the history of coal that used the metaphor of the genie who grants wishes.

Burning coal to release the energy within provided us with previously unimagined material riches. But, there was a price to pay.

Both mining it and burning it made some people sick and killed others. Coal fire pollution was so bad that early industrial centers passed the world’s first pollution abatement laws.

The genie metaphor works for credit expansion banking too.

Yes, expanding the money supply allows the economy to grow.

But, due to the very nature of how they work, no credit expansion banking system is immune from “too many” defaults and bank runs.

And in the same way that peanut butter does not exist without peanuts, credit expansion banking systems do not exist without business cycles, without booms and busts. I’ll talk more about that in a future post, but for now, understand the booms and busts of the business cycle are “baked into” credit expansion banking systems.

How do they work?

It’s very simple really, but not intuitive.

When we borrow money from a bank, it seems intuitive that the money “comes from” somewhere.

But it doesn’t.

After the bank determines you’re a good credit risk and you’re likely to make all the required payments on time, they create a contract known as a loan agreement.

The loan agreement specifies how much is being borrowed, when payments start, how much the monthly payment is, and how many months payments will be made for.

While this next statement may seem counter intuitive, the bank then buys that loan agreement from you.

They give you a lump sum of money now, in exchange for payments per the loan agreement later.

And they money they buy the loan agreement from did not exist prior to them buying it.

They specifically create a deposit account for you, and “mark up” that account (by literally typing numbers into a ledger) by the amount of the loan while simultaneously entering the repayment schedule into their system.

Two ledger entries get created.

The deposit is an asset to you and a liability to the bank (because you can withdraw it at any time).

The loan is a liability to you (as you’ll be making the monthly payments) and an asset to the bank (as they’ll be receiving those payments).

As the loan is as asset, it is something that is owned. Initially it is owned by the bank that issued it.

However, it can be sold, and loans often are.

You’ve seen this if you’ve ever taken out a mortgage with Bank A then shortly thereafter received a document from Bank B information you that you’ll be paying them from then on.

If loans create money, do loan payments destroy money?

Yes, they do.

As the use of credit in an economy expands, the money supply expands. As credit is paid down, the money supply contracts. That is THE basic principle of a credit expansion banking system.

How does this create the business cycle?

I think this post is long enough, so that will be the topic of my next post.