What inflation and quantum mechanics have in common

If you think you understand them, you probably don't

“Is everyone pretending to understand inflation (or just me)?” - Professor of International Political Economy Mark Blyth

“If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don't understand quantum mechanics.” - Theoretical Physicist Richard Feynman

To be fair, I did not hear Professor Blyth say the above quote. It is however the title of a podcast episode in which he talks about inflation1, that was published on September 20, 2024.

This post is a terse summary of that interview, with a very slight detour.

Mark Blyth is one of my favorite story teller economists, as he understands the importance of stories to how we humans understand, well, anything.

In this interview he reviews a few commonly held beliefs (stories) about what causes inflation. The genesis of these stories are from the inflation of the 1970s, and were “dusted off” to explain the inflation of the 2020s.

Overview

At best, each story provides a partial explanation.

But first, for purposes of this post, we’re using the definition of inflation provided by Professor Blyth during the interview. It consists of two parts:

A general rise in ALL prices.

When inflation is lower, it does not mean prices go down, it means that the rate at which prices go up, is lower.

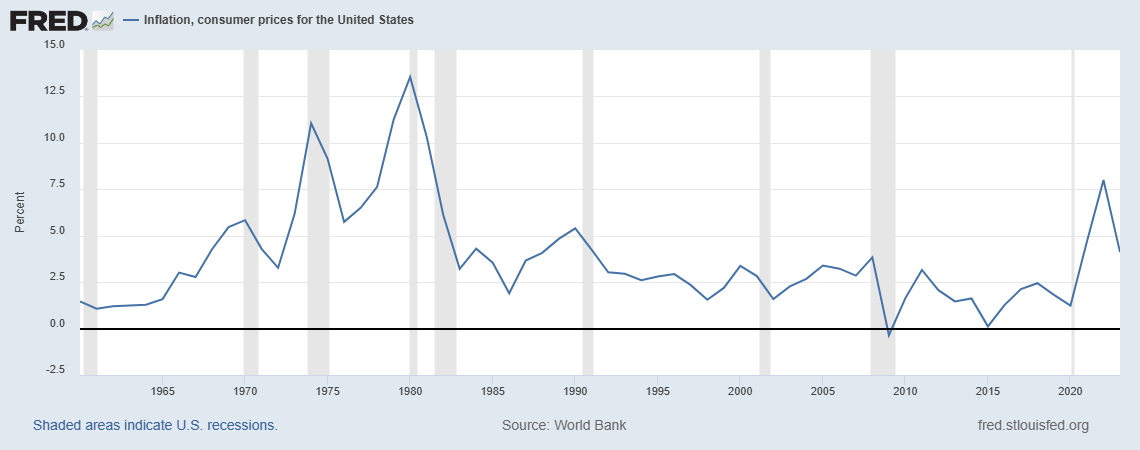

Below is a chart, from the FRED data repository, of the US inflation rate from 1960 to 2023.

From the 1970s: What caused inflation?

Professor Blyth spoke about a few main stories with which we explain what happened.

Story #1: The wage price spiral

A combination of increased government spending for social safety net programs and the Vietnam war, combined with a significant number of working age men being drafted for that war, created a situation where unemployment plummeted creating a super tight labor market.

As a result of increased competition for available workers, wages rose, leading to higher incomes, leading to increased demand, leading to higher prices.

Then “future expectations” of even higher prices caused increased wage demands and occurrences of strikes, which resulted in increased wages, which caused increased demand, which caused higher prices, which caused increased wage demands, etc.

The story of how to fix things was that pushing interest rates up to very high levels would create a few years of high unemployment followed by good times.

“And then after that, for a long period, we had pretty low inflation and pretty high growth. So the story of the 70s was that’s what happened, government bad, markets kind of good, government can’t be trusted, spend too much money, Federal Reserve good, independent, keep them away from the politicians, push interest rates up, crush the economy, sorry unemployment, but don’t worry it’ll only be two years, and then everyone will be fine. That was the story. And everything is interpreted through that model.”.

But professor Blyth feels that story is incomplete.

Story #2: Greater labor participation increased demand

The labor shortages caused by the Vietnam war (half a million people in Vietnam, two million in support) created a dynamic where women and minorities joined the labor force, at scale, for the first time.

This had the effect of segments of our population receiving either wages at all, or received higher wagers than before.

This increase in aggregate wages created more consumer demand. More consumer demand meant higher prices.

Story #3: Supply shocks

Failed wheat harvests in the USSR (1971) and Canada and the USA (1972 - 1973) caused wheat and everything containing wheat to be more expensive.

Due to the OPEC oil shock of 1973, the price of a barrel of oil rose from $4 to $16. As a result, everything whose production and distribution depended on oil (i.e.: everything) got more expensive.

Shortages of energy and goods rippled through the economy.

In aggregate, supply shocks of various basic goods lasted about a decade.

There was not a decade long shortage of any one commodity, but as the supply of basic commodity A returned to prior levels, we were hit with a shortage of basic commodity B, etc.

From this perspective, the high interest rates imposed by the Federal Reserve were not only unnecessary, they made things worse. They made the recession longer.

As supply shocks were alleviating, a sharp increase in interest rates put a damper on the economy above and beyond what the supply shocks themselves provided.

From the 2020s

Story #1: The government spent too much money

The Covid stimulus checks pushed us over the edge. Too much money was placed in the bank accounts of consumers, demand went up, prices went up.

However, where that story seems to fail is that countries that did not mail out stimulus checks had just as much inflation.

Story #2: Too much employment

A couple years after the Covid shutdown, unemployment plummeted to the lowest levels in 50 years, people were making more money, which increased demand, which increased prices.

This is similar to the wage price spiral story.

Story #3: Corporate greed

Also known as greedflation or sellers inflation.

Evidence to support this story is that many large company CEOs and CFOs were announcing record earnings in their quarterly investor calls.

This indicates those corporations had increased their prices above what was needed to cover their increased costs.

Story #4: Supply shocks

Covid disrupted global supply chains and we ran out of a lot of basic necessities.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine drastically reduced Ukrainian wheat exports.

EU sanctions on Russia drastically reduced the flow of Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) from Russia to various parts of Europe, especially Germany. The destruction of sections of the Nord Stream pipelines ensured Russian LNG could not start flowing again.

Reduced energy supply caused an increase in energy prices, which caused an increase in the price of everything.

These stories are not mutually exclusive of each other

In fact, it seems plausible that each of the four stories contributed some to the inflation of the 2020s.

But different people latched onto and shared different stories.

Simple stories

We seem to love simple stories. And people seem to be attracted to the story that most matches their political beliefs.

And maybe we aggregate too broadly

Here I’m taking a detour from the Mark Blyth interview and bringing in information from a podcast episode with Steve Keen.

We like to collapse “inflation” into a single number, either the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) and MAYBE, just maybe, collapsing inflation into a single number is, in and of itself, a problem.

Maybe aggregating into one single metric is too coarse, too broad.

As I mentioned earlier, this is something Steve Keen discussed on a recent episode of his Debunking Economics podcast, in an episode titled The Aggregation Problem2.

The detour mentioned above is now over and I’m now returning to the Mark Blyth interview.

Right now, a huge factor in “everything costs more” is rent is very high.

The demand for rental property greatly exceeds the supply, and prices rose.

But when the Fed raises the interest rate to slow the economy, doesn’t that slow down the building of new housing? Thereby keeping rents high?

How immigration and tariffs affect inflation

Immigration

If Donald Trump wins the 2024 Presidential election and follows through on his campaign promise of mass deportations of undocumented immigrants, two things are likely to happen:

There will be less competition for the types of jobs these undocumented immigrants do, which tend to be lower paid jobs in agriculture, food services, constructions etc. As those jobs will now be filled by documented people demanding higher wages, wages for these jobs can be expected to rise.

As these wages rise, the businesses will need to cover their increased costs, so prices for their products and services can also be expected to also rise.

The increased wages for those workers will increase demand for things those workers want.

Tariffs

Again, if Donald Trump wins the election and imposes across the board 100% tariffs on all imports from China, everything we import from China, which means almost everything in Walmart and other large retailers, will double in cost.

Which MAY incent companies to move production to factories in the US, in order to avoid tariffs.

But even without tariffs, American made goods will be more expensive than Chinese made goods were before the tariffs were applied.

Which means…

Employing American workers and paying them more is a direct benefit to those workers, and the businesses paying those higher wages will likely increase their prices to cover their higher wage expenses.

So the plus is higher aggregate wages, and the accompanying minus is higher aggregate prices.

In closing

Inflation rarely has one single cause, and our idea that changing the federal funds interest rate is THE fulcrum around which the entire economy pivots is excessively simplistic.

In my humble opinion, it probably makes sense to aggregate to the level of the industrial sector (food vs housing vs energy vs healthcare, etc) and NOT to a single metric.

Then take appropriate legislative actions to create incentives to increase supply and or decrease demand (whatever makes sense for the specific sector at that time) within what would then be clearly seen as the sectors in which there are problems.

It always pays to study the causes of any particular inflation problem. And of course there is a right answer. Unfortunately, the problem lies in the politics.

Australia Institute research has shown that current inflation in Australia is profit driven ['greedflation'] - (a conclusion supported by the OECD)

https://australiainstitute.org.au/post/challenging-the-consensus-on-profits-and-inflation/

https://futurework.org.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/02/Profit-Price-Spiral-Research-Report-WEB.pdf

"Analysis of the income flows associated with excess inflation since end-2019 confirm the

dominance of corporate profits in the acceleration of inflation since the pandemic.

Excess corporate profits account for 69% of additional inflation beyond the RBA’s target."

But conservative arguments taint Treasury's response: https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-07/foi-3376.pdf

The title of the post rings true and may be it is time for Occam's razor. The apparent weirdness of Quantum Mechanics stems from the quaint picture that particles make detectors go 'click'. Q.M. predicts only the probability of the outcome of a measurement. Prior to the measurement, the particle's very existence like Schrodinger's dead and alive cats is purely a matter of philosophical speculation.

One can make a similar statement about inflation. Prices rise and inflation occur for one observable reason: businesses tick up their price labels. Conservatives and progressives will only agree on just that one thing. Any cause, perceived or actual, is muddied by politics. Indeed, governments as issuers of the currency can do a bunch of things to deal with inflation [Job guarantees and price controls]. What they do is a matter of politics.