It surprises me that the question “for who?” is not asked more often in relation to statements made regarding what is good and bad in economics reporting.

There are two sides to every transaction. Every purchase, every loan, every everything.

And it’s not uncommon for something that is bad for many people, to be good for others.

So whenever you hear that something is bad, or good, your immediate question should be “for who?”.

Inflation

Inflation is bad for consumers, as it erodes purchasing power over time. It’s especially bad for people living on fixed incomes, such as people living on disability or pension income, as they’ve stopped getting raises.

But if you’re making payments on long term debt, such as a 30 year fixed rate mortgage and you have 25 years to go and you anticipate earning more in the future than you do now, over time your mortgage payment will take up a smaller and smaller percentage of your monthly income. For people in this situation, inflation is good.

Deflation

So how is deflation worse, and for who?

First, let’s briefly acknowledge that the people living on fixed incomes mentioned above benefit from deflation. For them, it’s good.

But, people who produce stuff live within production cycles.

They generally buy production inputs (materials, labor, etc) with working capital loans, and pay off those loans post production.

For these people, deflation is especially bad.

Production cycles and bridge (working capital) loans

The concept of production cycles applies to farmers, real estate developers, and pretty much anyone who produces stuff where there are lag times between ramping up, production, selling, getting paid, and paying off the bridge loans.

But as all production cycles follow a similar arc, we need only use one to illustrate the concept.

I’ll use farmers.

Farmers generally take out loans with which to buy seed and fertilizer, pay for equipment and fuel, pay employees, etc.

Then when they sell their crops after the harvest, they pay off the loans.

Farmers generally take out the loan before planting and pay them back after the harvest is sold.

If, during that interval, there is a drop in the price of the crops they grow, what they receive for their crop might not generate profit, or even enough to pay back their loans.

And this has happened.

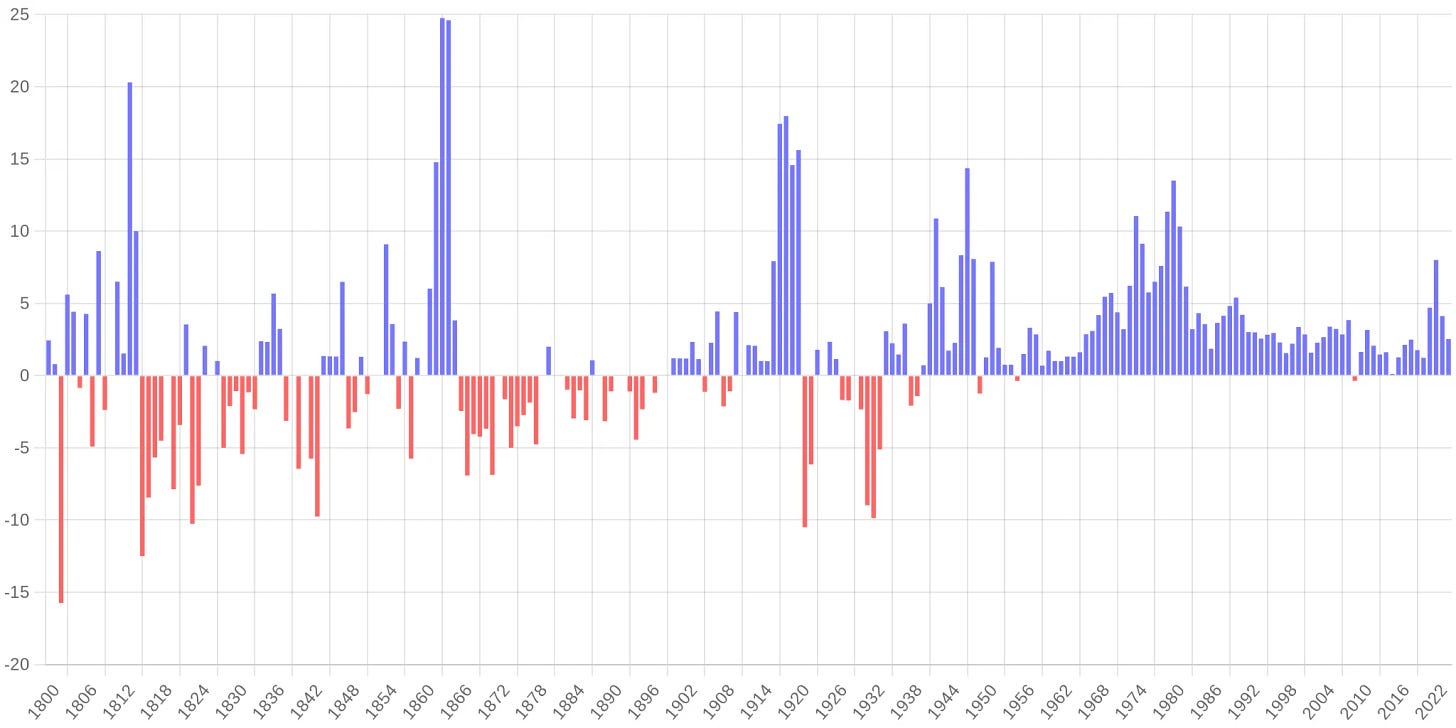

The chart below shows inflation in the USA from 1800 to 20241. Each bar represents one year.

As you can, not only did deflation (the red lines below the zero line) used to be common, but fairly extreme price volatility used to be common.

Why?

Price volatility is inherent in commodity money

People who are nostalgic for the gold standard seem to be unaware that price volatility is an inherent characteristic of commodity based money.

This is because the price of everything is expressed as the ratio of quantities of commodities to the quantity of the money commodity, and the quantity of the money commodity fluctuates23.

One of the most interesting aspects of gold standard price volatility was when the money supply changed as a result of settling balance of payments between countries, by moving gold between countries.

When one country, say the United States, exported a lot of goods to another country, say the United Kingdom, the balance of payments was settled by gold moving from the UK to the US.

This decreased the money supply in the UK and increased the money supply in the US4.

As a result, the ratio of gold to everything in the UK fell, so prices in the UK fell, whereas the ratio of gold to everything in the US rose, so prices in the US rose.

All because some US businesses had a good year exporting to the UK.

But isn’t our true wealth what we produce?

Yes, and therein lies the big deflation problem.

Economists sometimes use the phrase “downward pressure” to indicate that something has a dampening effect on something else.

Deflation exerts downward pressure on production5, and does so in various ways.

I also wish to be clear that the ways in which deflation decreases production are not isolated from each other. As is common in analysis of macroeconomics, everything is a cause of some things and an effect of other things.

Demand slows

If goods are likely to cost less later than they do today, it makes sense to wait to buy it later, when it’s cheaper. This results in lower short term demand and sales for businesses, as well as increased unsold inventory.

Production slows

Since less is being sold, less needs to be produced.

Margins shrink, bankruptcies increase

Lower margins in and of themselves is a problem for businesses, but for some firms living near the edge of solvency, it can be catastrophic.

Because of this, during periods of deflation, business bankruptcies increase6.

Debt “costs more”

Above, I mentioned how inflation works to the advantage of people who are paying on long term fixed rate debt, such as a 30 year mortgage.

Deflation works to the disadvantage of debtors.

When a farmer owes money on a loan, and the crop they sell drops in price, it’s harder to pay off that loan. In some cases they may not be able to pay off that loan7 at all.

The worst? Deflationary spirals

In extreme situations (the great depression for example) all of the above can contribute to what is called a deflationary spiral8.

When this happens things go from bad to worse to worse, until such time as whoever manages monetary and fiscal policy for the nation takes action to increase price levels, by whatever means necessary.

Because few things are as damaging to an economy as a deflationary spiral.