Background

In what I’ll generically call “the west”, the term “free market” is used in the context of free markets vs regulated markets, where regulation is “government intervention”.

This framing implies the more regulated a market is, the less free it is.

So, to make markets more free, we regulate them less.

And while I’m accepting of this general idea, perhaps because I’ve been steeped in it my entire life, if you extend to the idea to it’s logical limit, it becomes absurd.

If less regulated markets are freer markers, then the freest market of all is one with no regulation.

And the absurdity of this is unregulated markets do not, have never, and can not, exist

Not only do all markets have rules, markets NEED rules.

Even where society breaks down, or “black markets” include criminal activity and contracts are enforced with guns, there is a general understanding of how things work. Even those markets have rules. And whoever makes those rules is in effect the regulator of that market.

So it seems to me, some important questions should be asked, but rarely are:

What should the rules be?

What rules achieve our desired goals?

And what rules impede them being achieved?.

Of course, those question presuppose a common understanding of “our desired goals”.

So this post is a romp through history, examining ideas of how we thought about the rules for markets for different periods and people in the past, leading up to how “free markets vs regulated markets” became a dominant idea today.

This post is somewhat based on the book Free Market: The History of an Idea, by Jacob Soll, and where direct quotes appear below and are not attributed to any other source, they are from this book.

Rome

Cicero, who lived in the period where Rome was transitioning from a republic to an empire, wrote some about economic ideas. He was pro trade, pro markets, pro ethical exchange, but for the nobility of which he was a member.

He wrote that the ultimate goal of economic activity was to serve the state and promote the common good. He saw civic service as the "Supreme Good" that should guide economic behavior.

Early Christian Church

As Christianity spread through the Roman Empire, Rome started changing from an empire into a church.

The afterlife became all important, salvation was available to those who were righteous, and the rules of commerce became focused on treating others right, as salvation depended upon it.

Markets were thought to be guided, as all of nature was, by divine rules.

Medieval Europe

As government structures degraded, the idea of markets as “within nature” and “guided by divine rules” faded.

Human inventions mattered more.

The heavy plow (9th century), double entry bookkeeping (13th century), etc, helped fuel the idea that WE (the aristocracy more than the peasants) make the rules.

This period saw the development of guilds, which tended to have very strict rules.

Florence

During this period the idea of being free to pursue the accumulation of wealth came into favor.

It was acknowledged that while markets existed all over Europe, they did not all produce wealth, and an idea started that institutional support was necessary for commerce and investment to flourish.

This seems to be the beginning of the idea that state support for free trade was necessary for commerce to create wealth.

England and State Supported Free Trade

“Sixteenth and seventeenth century economic thinkers constantly stressed that wealth production required a mix of investment and individual enterprise.”.

This seems to be when when and where the idea of states directly supporting markets and industries started to take hold.

The Dutch and State Supported Free Trade

“However precocious this free market thought may appear in hindsight, it, too, like English and French economic thought, operated on the assumption of a heavy dose of government involvement in the economy. The realities of politics and imperial economics did not always fit nearly into the ideas of freedom espoused by Dutch republican thinkers. As during many other periods of history, free market ideas coexisted with the more complex reality of state interventions.”.

The Pace Quickens

Starting with the next section, the pace of changing from old ideas to modern ideas quicked.

State Made Markets in France

Many dynamics, ideas, institutional structures, etc between governments and markets that exist today started in France in the 17th century.

Jean Baptist Colbert1 has shown up in a few different books I’ve read about the history of economics, money, commodities, trade, etc.

He was a French aristocrat who served in the government of King Louis XIV and has been described as “his de facto prime minister”. He served Louis XIV from 1665 until his death in 1683.

As Europe was developing a sweet tooth, he seems to be “the guy” who established the rules for French colonial sugar production, which other colonial powers later emulated.

But first he established rules and structures to improve trade and commerce within France, then carried them over into colonial productions.

Like what?

National industrial standards

Uniform weights, measures, and product naming

State inspections to enforce the above

State support (money) for new businesses

Building maritime cargo ports

Tariffs to protect some industries

Standardized accounting rules

State support (money) for science and basic R&D

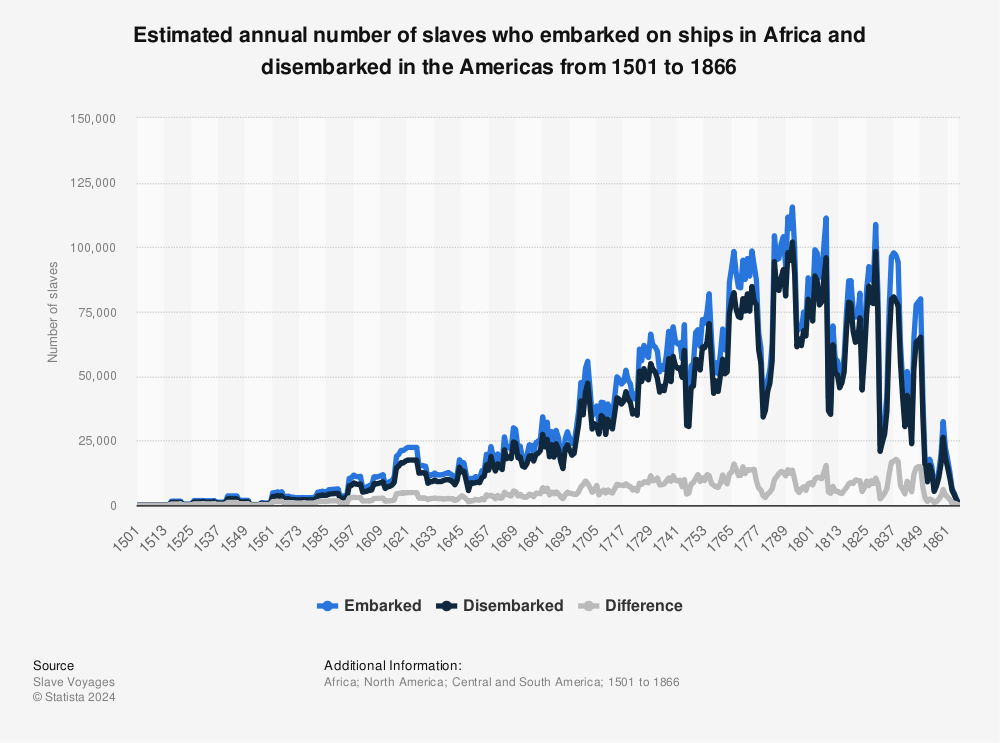

These rules and structures were “exported” to facilitate production in France’s colonies, which also included rules for, and the ramping up of, the African slave trade.

To us, the idea that “free markets” including the buying and selling of enslaved people seems like a contradiction. To them, enslaved Africans were considered to be a necessary input to production.

As you can see in the chart below, his time in office corresponds to when the “harvesting” of enslaved Africans started to rise dramatically.

Why? Sugar production.

When other European colonial powers saw what types of rules and institutions France was having commercial success with, they copied them.

Paper Banknotes, aka France vs England

Neither France nor England were the first European countries to issue paper banknotes. Sweden was, in 16612. Having said that, China had been using paper money since the 11th century3.

But France and England scaled up the issuance of paper banknotes to previously unseen levels in an effort to expand their markets. But, the creation of this new money fueled two massive frauds, one in each country.

France: The Mississippi Company

There are many sources on the Internet where you can read up on John Law, the Banque Royale, and the Mississippi Company, so I will not repeat that history here.

What’s significant in terms of “free markets” was that in the early 18th century in France the concept was expanded to include:

A private bank (Banque Royale) that acted as a central bank, with the ability to issue banknotes on a fractional reserve banking system, the right to mint coins, and the right to collect almost all French taxes.

A company (The Mississippi Company) granted a 25 year monopoly on economic activity in New France, which at that time extended from Mississippi to Labrador.

And most interestingly, rules that allowed people to borrow from the Banque Royal to buy shares in the Mississippi Company.

As a result of the above, the following happened:

The money supply greatly expanded as the Banque Royale made loans.

The world’s first known asset bubble: As a result in speculating with borrowed money, shares in the Mississippi Company rose far far far in excess of their revenues and cash flow.

The man who organized all this was a Scottish financier named John Law. His basic insight was that money per se is not wealth, but rather is a catalyst for producing wealth.

That insight has since been proven correct by the fact that after “credit expansion banking” became prevalent in Europe, economic prosperity expanded to previously unimaged levels.

But The Banque Royale and The Mississippi Company were our first attempts at creating real wealth through expanded production by virtue of credit expansion banking (debt), and in this first attempt, we screwed it up royally, pun intended.

England: The South Sea Company Bubble

A few years prior to the issues with the Banque Royale and the Mississippi Company, England tried something similar.

For what it’s worth, the Bank Generale was opened in France in 1716, the Mississippi Company (the Compagnie d'Occident) was formed in 1717, a monopoly was granted to the company in 1718, and the bank was taken over by the French government and renamed the Banque Royale in 17194. The stock price bubble started in January of 1719 and the crash was over by September of 1721.

The South Sea Company in England was formed in 1711, a monopoly was issued in 1713, and the entire mania, panic, and crash was done by 1720.

So why does history record The Mississippi Company as the first known asset bubble and not The South Sea Company?

I don’t pretend to know for sure, but I suspect it has to do with history being written by the victors, and England becoming the global empire instead of France. But this is speculation on my part.

Anyway, near as I can tell from what I’ve read, the South Sea Company was pure fraud.

The book The South Sea Bubble, by John Carswell is a fascinating read.

As would soon happen in France, the idea of “free markets” was expanded to include:

A large company with a monopoly (The South Sea Company).

The expansion of the money supply through credit expansion banking (debt).

The ability to buy shares in the company with borrowed money.

And as you can image it was the usual mania, panic, and crash that asset bubble inflation and deflation causes.

But, most importantly, the idea of “free trade” was forever expanded to include government operated banks, credit expansion banking, and government support (tariffs and subsidies) for private companies.

The Enlightenment Age Cult of Nature in France

Something I think of as truly profound happened in France in the mid 18th century, but sadly was quickly forgotten.

A group of French economists who came to be known as the physiocrates promoted the idea that all wealth starts with “the free gifts of nature”.

That feels fundamentally right.

All the foods we eat started as stuff we found growing wild. The energy resources (coal, oil, natural gas, nuclear, etc) were not created by us, they were/are mined by us. We found them and figured out how to exploit them.

All goods we manufacture are created from raw materials found in nature and we learned how to modify them, in some cases in extreme ways, to our advantage.

But the physiocrats also said that manufacturing did NOT produce wealth, only agriculture did, and that is clearly wrong.

They recognized that labor turned the free gifts of nature into wealth, but the free gifts of nature is where it all starts.

They also believed markets need state support, the creation of standardized weights and measures being one such example.

Free Markets vs Nature in Italy

As manufacturing grew in Europe, the physiocrats were thought to be a little weird (which is probably a fair assessment).

Some people in Italy sought to build up industry following the template setup by Colbert almost a century earlier.

The idea that free markets involved “government support and intervention” including legal and financial support, grew stronger.

Adam Smith

In 1776 Adam Smith published his famous book The Wealth of Nations.

It is considered to be the first published book of economic thought, which is not literally true as he had previously read books published by others, but again, history is written by the victors, and he was British.

While Adam Smith is often portrayed today as a champion of laissez-faire economics and a proponent of minimal government regulation, his views were not seen so simplistically in the 18th century.

Below, I pull quotes from The Wealth of Nations to show ideas he had on rents, monopoly, and government regulation. The copy I have was published by The University of Chicago Press and was published in 1976.

Rents as extraction

I think one of his great insights of his is that the price we pay for something consists of three broad categories, wages, profits, and rent.

Smith wrote that wages and profit add value (add to production) whereas rents extracts value by diverting resources away from production.

“As soon as the land of any country has all become private property, the landlords—like all other men—love to reap where they never sowed, and demand a rent even for their land’s natural product.”.

“So the rent of land, considered as the price paid for the use of the land, is naturally a monopoly price.”.

“Whatever part of the product—i.e. whatever part of its price—is over and above this share the landlord naturally tries to reserve to himself as the rent of his land, which is obviously the highest the tenant can afford to pay in the actual circumstances of the land.”.

“He sometimes demands rent for what is altogether incapable of human improvements.”.

“So rent enters into the composition of the price of commodities in a different way from wages and profit.”.

In his day “rents” meant the rent of land with or without buildings. These days “rents” is used to mean “unearned income” or income received by virtue of ownership rights. Bonds that pay interest, stocks that pay dividends, etc.

While the phrase “rent seeker” does not appear in the Wealth of Nations, from his writing it seems clear he saw people seeking unearned income (rents) as extracting from production and as economic parasites.

Monopolies

“A monopoly granted to an individual or a trading company has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists—by keeping the market constantly understocked, never fully meeting the effectual demand—sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their income, whether it consists in wages or profit, greatly above its natural rate.”.

“The price of monopoly is always the highest that can be got.”.

So, it seems he was not a fan of monopolies.

Government Regulation

So, how are people who wish to extract high rents and people who wish to form monopolies kept in check?

Regulation. In his writing, regulation was neither good nor bad per se.

Regulation that restricted competition was bad, while regulation that encouraged competition and restricted rent seeking was good.

Free markets need regulation

Essentially, Adam Smith seems to have written something I opened with at the start of this post, which is that all markets have rules. Unregulated markets do not in fact exist, and what the rules are matters.

The American Era

We are now leaving behind the book Free Markets mentioned above, because while the book continues for a chapter or two, it’s doesn’t segue into “And then the Americans started making the rules”, which they did.

The Navigation Acts

For some reason, the restrictions The Navigation Acts5 placed on what trade the British colonies could and could not participate in is not emphasized in US history.

But those restrictions were significant to the business leaders in the American colonies.

They prevented the American colonies from exporting to, or importing from, any destination or country other than Great Britain6.

This resulted in a fundamental disagreement on what the rules of free trade should be.

It’s common in discussion of economics to say something is good or bad, without further clarifying good or bad for who.

The Navigation Acts were good for Great Britain in aggregate, but not so good for their overseas colonies.

And they are considered to be one of the significant causes of the American independence movement7.

WW1 and a Redefinition of What Free Markets Mean

There are three main aspects of how global trade changed in the aftermath of WW1 that I think are worth mentioning here.

Modern nation states replaced empires as the dominant geopolitical entities.

Global trade fell about 66% from 1929 to 1934. This is attributed partly to tariffs and partly to the depression.

The USA emerged as the dominant global rule maker.

And…

Economist Michael Hudson8 teaches that a fundamental redefinition of the phrase “free markets” occured around the time of WW1.

The quotes below come from an interview9.

“The classical economists were almost diametrically opposed to the kind of economics that’s taught today. That is why it’s not taught in economics courses anymore. The ideas of the classical economists, from the Physiocrats to Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill and his followers, were to free economies from the landlord class. The classical economists wanted to develop Britain, France, Germany and other countries industrially. They thought that the only way of becoming industrially competitive was to minimize the free lunch taken by the landlord class in the form of rent – income that rent recipients make in their sleep, as Mill put it. The classical economists also aimed to get rid of monopolies, which obtained monopoly rent much like land rent. This aim involved getting rid of financial rents and natural-resource rents also.”.

“The idea was to free economies from having to pay such rents so that their costs would only involve paying people who actually contributed to the production process.”.

Question: “Okay so what was a free market for Adam Smith?”.

Answer: “The free market was a market free from economic rent. It brought prices in line with actual cost-value. Rent is the excess of price above value, and it was to be minimized, so as to make economies free from interest and from the ability of the landlord class – in Smith’s day the main rentier class – and also the financial class. These elites sought to wage or finance wars, to try to grab more land, to get more land rent, to create monopolies and business plans that essentially were exploitative. Adam Smith wanted a free market from the rentiers, whereas the neoliberals want a free market free from the government and for the rentiers.”.

And per Michael Hudon, this change is definition from “free from rentiers” to “free for rentiers” occured around the time of WW1.

And this paragraph is especially interesting, at least to me.

“But it turns out that economics students in America don’t learn how America got rich. That’s not taught anymore; that’s classical economics. They are taught about how to go to business school and load the economy down with debt, and avoid protectionist policies.”.

WW2 and the Birth of The International Order

As WW2 was winding down, representatives of many nations allied to the USA met to hammer out The Bretton Woods System10.

It created international institutions for defining rules for markets. Two such institutions are The World Bank11 and the International Monetary Fund12.

One core idea was that fixed exchange rates would encourage global trade. To that end, the rules of global free trade were adjusted to include13:

Gold was money

The US dollar was pegged to gold at $35 an ounce

Every other currency was pegged to the US dollar at a fixed exchange rate

The End of the Gold Standard

But in 1971, some nations presented gold certificates to the US Federal Reserve such that a good old fashioned bank run drained the US gold reserves, which the Bretton Woods System was built on.

So in 1971, the US abandoned the gold standard14 for the last time (it had happened for periods of time in the past), at which time the rules of global free trade were again adjusted, but this time to include:

Fiat currencies

Floating exchange rates relative to other fiat currencies

Neoliberalism

The rule changes put in place when WW1 was coming to a close, where markets were being made free from government regulation for the benefit of rent seekers, did not fully displace prior schools of thought right away. That took several decades.

But in the late 1970s and early 1980s, that idea was folded into a larger set of rule changes known as neoliberalism15, which dominates economic policy to this day.

Some of the defining characteristics of neoliberalism are:

Free trade stands in opposition to heavily regulated markets and protectionism

Less government control enhances the efficient functioning of free markets

Both of which separate the idea that markets should be regulated from the reality that all markets have rules.

The following quotes are from the book The Secrets of the Temple by William Greider, published in 1987 by Simon & Schuster Inc.

In the Reagan era’s ethos of free markets and less government, there was no prospect that politicians of either party would pursue this solution [forms of credit controls]. Indeed, the political influence of commercial bankers was pushing in the other direction - toward greater freedom from legal restraints. The largest banks sought the power to operate nationwide, a consolidation of financial power that would inevitably centralize the political influence of banking in a handful of very large institutions. They lobbied for the right to enter into other business sectors - where they would enjoy enormous advantages over competitors since they would be protected from failure by the federal government, thanks to the special stats as commercial banks.

pp 665 and 666

The only voices persistently and persuasively raised in behalf of restoring credit controls were, ironically, from major investment-banking firms of Wall Street - the conservative citadels of capitalism. Financial experts like Henry Kaufman, Albert Wojnilower, Philip Braverman and others warned repeatedly of the risks of the debt explosion and proposed various ideas for imposing new legal limits on lending.

None of their proposals received any serious examinations in Washington. Strange as it may seemed, leading gurus of Wall Street were urging the federal government to impose new discipline on finance and the leaders of government in Washington would not listen to them. It was another measure of how much the mainstream political opinion had shifted. In the political capital, the new mythology held that the federal government had at last gotten out of the business of regulating finance. And the free market was producing all the benefits predicted for it.

The Wall Street economist knew it wasn’t so. The free market was always itself a fiction.

The emphasis is mine.

p 666

In closing

For classical economists, the rules were made by governments to keep bankers and industry leaders from consolidating “too much” power.

For neoliberal economists, the rules are made by bankers and industry leaders to keep governments from preventing the consolidation of corporate power.